This past spring I wrote

a four-part series on the return of the Pennsylvania Reserves to Northern Virginia at the start of 1863. This storied division had experienced heavy losses during the previous year's fighting, and after political intervention by top-ranking generals and Pennsylvania's own governor, the Reserves were sent to the defenses of Washington to rest and recruit. As June 1863 began, the division was scattered across Northern Virginia and Washington City. The month would end with two-thirds of the division on the march north to join the Army of the Potomac in pursuit of Gen. Robert E. Lee's Confederates.

A New Commander and a Return to the Old Dominion

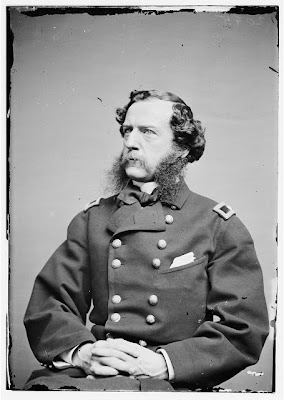

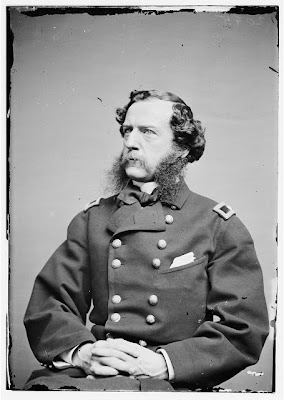

On June 1, 1863, Gen. Samuel P. Heintzelman, commander of the Department of Washington, named Gen. Samuel W. Crawford to replace Col. Horatio G. Sickel at the head of the First and Third Brigades of the Pennsylvania Reserves. (

OR, 1:51:1, 1043.) The Second Brigade was to remain attached to the Military District of Alexandria. Heintzelman ordered Crawford to make his headquarters at Fairfax Station, where the First Brigade was encamped. The Third Brigade, which was performing provost duty in Washington City, was directed to cross the Potomac and proceed to Upton's Hill, not far from Falls Church.*

|

| Brig. Gen. Samuel W. Crawford (courtesy of Library of Congress). Crawford was born in Franklin County, Pennsylvania in 1829. He was the surgeon in charge at Ft. Sumter during the bombardment in April 1861. Crawford joined the Union infantry and rose to brigade command by spring of 1862. He briefly led a Twelfth Corps division at Antietam until being wounded in the thigh. Following his recovery, Crawford was given command of the Pennsylvania Reserves. |

On the evening of June 1, the men of the Third Brigade under Col. Joseph W. Fisher marched out of the city "to the sounds of martial music." (Columbia Spy, June 6, 1863.) The soldiers "were in fine spirits," and "cheered as they passed through [the] streets, glad again to be in the field." (Phila. Press, June 2, 1863.) Spectators along the sidewalk and in hotel windows echoed the soldiers' hurrahs for Ulysses S. Grant, Joseph Hooker, George B. McClellan, William Rosecrans, and other generals. (Columbia Spy, June 6, 1863.)

Rallying to the Defense of the Keystone State

Events soon took an alarming turn. As talk of a Confederate invasion of Pennsylvania spread, the Reserves grew anxious to leave Northern Virginia and defend their native soil against Lee's army. According to one regimental history, the thought of remaining behind in the defenses of Washington "was rather mortifying." (Woodward,

Our Campaigns, 259.) Officers made entreaties to Washington and Harrisburg to have the Reserves return to the field along with the Army of the Potomac. In one instance, the commander of the 2nd Pennsylvania Reserves and his fellow officers petitioned Col. William McCandless, head of the First Brigade:

We, the undersigned. . . having learned that our mother State has been invaded by a Confederate force, respectfully ask, that you will, if it be in your power, have us ordered within the borders of our State, for her defence.

. . . we have more than once met and fought the enemy, when he was at home. We now wish to meet him again where he threatens our homes, our families and our firesides.

Could our wish in this behalf be realized, we feel confident that we could do some service to the State that sent us to the field, and not diminish, if we could not increase, the lustre that already attaches to our name. (Woodward, Our Campaigns, 260.)

McCandless received the petition on June 17 and "forwarded it through the proper channel to Washington." (Woodward,

Our Campaigns, 259.) Meanwhile, Gens. John F. Reynolds and George G. Meade, who had both led the Reserves through the bloody trials of 1862, requested that the War Department transfer the division to their respective army corps. (

See, e.g., Sypher 448; Thomson & Rauch 260; Woodward,

The Third Reserve, 226.)

At Last! -- Rejoining the Army of the Potomac

The fate of the Reserves became part of the larger question of reinforcing Hooker as he chased down Lee's army. General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck, worried about keeping the nation's capital safe from a possible Confederate advance, maintained a tight grip on the soldiers belonging to the defenses of Washington. (Coddington 96.) In the end, Halleck relented and agreed to send Hooker around 8,400 infantry reinforcements, including two brigades of the Pennsylvania Reserves. (Sears 220.)**

Late on June 23, Hooker directed Crawford "to hold [his] command in readiness to move at very short notice," with ten days' subsistence. (

OR, 1:27:3, 273.) Pickets were to remain posted "until further orders." (

OR, 1:27:3, 273.) Less than two days later, Hooker put the Reserves in motion to catch up with the rest of the army, which was already in pursuit of Lee. At 9:30 in the morning on June 25, Crawford was directed to "march with your command to-day, via the Leesburg turnpike, to Edwards Ferry, and, if possible . . . cross the river at that point, should you reach the Ferry in season." (

OR, 1:27:3, 309.)

Not long afterwards, Hooker was shocked to learn from Crawford that John P. Slough, military governor of Alexandria, had detained the Second Brigade of Pennsylvania Reserves. He fired off a note to Halleck, demanding that "General Slough be arrested at once" and promising that "charges will be forwarded as soon as I have time to prepare them." (

OR, 1:27:1, 56.) Hooker sharply warned Halleck, "You will find, I fear, when it is too late, that the effort to preserve department lines will be fatal to the cause of the country." (

OR, 1:27:1, 56.) The General-in-Chief wasted no time in brushing aside Hooker's request:

The Second Brigade, to which you refer in your telegram, forms no part of General Crawford's command, which was placed at your orders. No other troops can be withdrawn from the Defenses of Washington. (OR, 1:27:1, 57.)

That same day, the First and Third Brigades struck camp and began their march from Fairfax Station and Upton's Hill.*** The soldiers proceeded as far as the area around Vienna, where they bivouacked for the night. (

OR, 1:27:1, 143; Woodward,

Our Campaigns, 261). Early the next morning the Reserves resumed their march. The Pennsylvanians moved up the Leesburg-Alexandria Turnpike, past Dranesville, where many of them had first experienced battle.**** A "violent and constant" rainfall turned the roads into "almost knee-deep" mud. (Woodward,

Our Campaigns, 261.) Despite such miserable conditions, the division reached Goose Creek that night. (

OR, 1:27:1, 143.) At daylight on June 27, the Reserves headed a short distance to the Potomac and crossed the river at Edwards Ferry via pontoon bridge. (

OR, 1:27:3, 353.) The division pushed through Maryland and arrived that night at the mouth of the Monocacy River, "in spite of the heavy roads." (Woodward,

Our Campaigns, 261;

see also OR, 1:27:1, 143.) Finally, on June 28, the Reserves crossed the Monocacy and marched to Ballinger's Creek near Frederick, where they joined the Fifth Corps. (

OR, 1:27:1, 144; Hardin 141.)***** By the time the Reserves caught up with the Fifth Corps, Meade had taken command of the Army of the Potomac, and Gen. George Sykes had replaced him at the head of the corps.

|

| Detail of Edwards Ferry, Goose Creek, and vicinity from 1862 Union Army map of Northeastern Virginia (courtesy of Library of Congress). The Leesburg Turnpike, also visible here, served as the Pennsylvania Reserves main route of march to the crossing at Edwards Ferry. |

The Pennsylvania Reserves continued their movement northward through Maryland and into Pennsylvania. The division arrived at Gettysburg on July 2 during the second day of the battle. That evening, the First Brigade drove into the Plum Run Valley and beat back an assault by troops from James Longstreet's corps on the Union left near Little Round Top. Crawford himself seized the colors and led the charge. The division's overall losses at Gettysburg stood at 26 killed, 181 wounded, and 3 missing. (

OR, 1:27:1, 180.) The Reserves had proven their mettle once again and made a contribution to the Confederate defeat. Before long, the Pennsylvanians would return with the rest of the army to the familiar soil of the Old Dominion. In this war, there was no staying away.

Notes

*The 11th Pennsylvania Reserves of the Third Brigade were still stationed in Northern Virginia in June, most likely in the vicinity of Vienna or Fairfax Station. (Gibbs 214-15.)

**The other units sent to Hooker from the Department of Washington included a brigade of New Yorkers under Gen. Alexander Hays and the Second Vermont Brigade under Gen. George Stannard. Both brigades would go on to distinguish themselves at Gettysburg. Halleck also agreed to furnish a division of cavalry under Gen. Julius Stahel, as well as artillery units, including the 9th Massachusetts Battery.

***The drive to replenish the ranks of the Reserves while in the defenses of Washington met with little success. (Gibbs 213; Thomson & Rauch 256-57.) The two brigades that set out on June 25 totaled just 3,817 officers and men. (Coddington 98.)

****The

Battle of Dranesville took place on December 20, 1861, and pitted a brigade of the Reserves against J.E.B. Stuart's Confederates.

*****The Pennsylvania Reserves officially became the Third Division of the Fifth Corps.

Sources

Aside from the

Official Records, the following sources were useful in compiling this post:

Civil War in the East (on-line database); Edwin B. Coddington,

The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command (1979 ed.);

Columbia Spy, June 6, 1863; Joseph Gibbs,

Three Years in the Bloody Eleventh: The Campaigns of a Pennsylvania Reserves Regiment (2002); Martin D. Hardin,

History of the Twelfth Regiment Pennsylvania Reserve Volunteer Corps (1890);

Harrisburg Daily Patriot and Union, June 27, 1863;

Philadelphia Press, June 2, 1863; Stephen W. Sears,

Gettysburg (2003); Jeffrey F. Sherry,

"The Terrible Impetuosity: The Pennsylvania Reserves at Gettysburg," Gettysburg Magazine, Issue No. 16, Jan. 1, 1997 (courtesy of P.R.V.C. Hist. Soc.); J.R. Sypher,

History of the Pennsylvania Reserve Corps (1865); O.R. Howard Thomson & William H. Rauch,

History of the "Bucktails" (1906); Evan M. Woodward,

History of the Third Pennsylvania Reserve (1883); Evan M. Woodward,

Our Campaigns (1865).

Additional Reading

An excellent and detailed account of the Pennsylvania Reserves' march from Upton's Hill/Fairfax Station to Edwards Ferry, including maps, can be found

here, at Craig Swain's Civil War blog,

To the Sound of the Guns. Also be sure to check out Craig's on-going series of posts on the march of the Union army through Loudoun County in the days prior to Gettysburg.

For the full story of the Pennsylvania Reserves at Gettysburg, see

"The Terrible Impetuosity: The Pennsylvania Reserves at Gettysburg," by James Sherry in

Gettysburg Magazine, Issue No. 16, Jan. 1, 1997.