Residents of the District sometimes view the Commonwealth of Virginia as though still belonging to the Confederacy. A few of my DC-based friends have even joked that they need a passport to cross the Potomac and enter the Old Dominion state. Governor McDonnell's original Confederate History Month proclamation did not do much to help matters. However, as even McDonnell was finally forced to recognize, the wartime reality of Virginia is much more complex and nuanced. Nowhere is this more evident than in Fairfax County.

Prior to the start of the Civil War, Fairfax and other parts of Virginia had seen an influx of Northerners, who were attracted by the milder climes south of the Mason-Dixon line. According to the1860 Census, the Northern states with the largest presence in Virginia were Pennsylvania (18,673), Ohio (7,735), New York (4,617), New Jersey (1,611), and Massaschusetts (1,431).

A November 1, 1861 New York Times article on Northerners in Fairfax County observed:

[When] the war broke out. . . they constituted a large and influential class of the population. They settled generally in the eastern part of the county, and are to be found most numerous between Drainsville [sic] and Alexandria. Groups of four or five families are to be found in other parts of the county, and between Centreville and Manassas Northern families are not unfrequently met.

The newcomers helped to improve farming methods and increase agricultural production in an area that had seen its fair share of economic hardship. As the Times reported, "[w]herever a Northern farmer bought a worn out farm two or three years sufficed to bring it up to an excellent condition." Moreover, "[t]he Northern settlers rarely buy slaves, but cultivate their farms with free labor. In some instances, where their sons have married into Southern families, they have become possessed of a negro or two; but in these instances, the relation has generally been one of a voluntary character." (I am not sure what is meant by "voluntary character;" perhaps the Times was trying to rationalize the contiunace of slaveholding by these Northern families.) The Times speculated that Northern industriousness had improved land values in the county. For example, an "estate of one hundred and forty acres, north of Falls Church, was purchased by a Northern man at $8; a year ago it would have readily sold for $75."

|

| American Farm Scenes, No. 2, Currier & Ives, 1853 (courtesy of The Old Print Shop) |

|

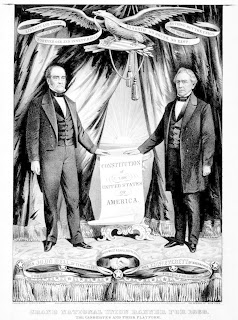

| 1860 campaign poster for the Constitutional Union Party. Presidential candidate John Bell is on the left; Vice Presidential Candidate Edward Everett is on the right (courtesy of Wikipedia Commons) |

As the country headed towards disunion, residents of Fairfax County initially hesitated to embrace secession. At least some of this sentiment is attributable to the presence of Northern transplants, as well as economic dependence on close-by Northern markets. During the election for delegates to the Secession Convention in February 1861, Fairfax's Unionist candidate, William Dulaney, received 57 percent of the vote, compared to the pro-secession candidate, Alfred Moss, with 43 percent. Dulaney was in the minoirty on April 17, when the Convention voted in favor of secession and sent an Ordinace to the voters for ratification. On May 23, 1861, Fairfax voters approved the Ordinance by 76 percent. Only three of fourteen districts (Accotink, Lewinsville, and Lydecker's, in and around Vienna) voted against secession. (See the original voting records here.) The start of hostilities at Fort Sumter and Lincoln's call for 75, 000 volunteers may have generated some of this support, which had grown considerably since the February vote. However, secessionists also intimidated voters at the polls, sometimes by openly threatening violence against pro-Union men. The voting was not by secret ballot, so everyone at a polling station would have known how a neighbor came out on the question of secession. Some voters likely switched allegiances or stayed home rather than risk physical harm to cast a vote against the Ordinance.

|

| "How Virginia Was Voted Out of the Union," Harper's Weekly, June 15, 1861 (courtesy of sonofthesouth.net) |

As the Union Army occupied Northern Virginia in the fall of 1861, the Times reported:

The Northern settlers are almost unanimous for the Union, and though they have suffered great losses by reason of the war, most of them having been compelled to desert their homes after Bull Run, they have aided the Union cause in every way they could. Some are acting as guides, others in various capacities under the Government.The paper also called out Northern transplants who supported the Confederacy, including the postmaster of Falls Church, who was arrested and forced to take an oath of allegiance. The postmaster fled to Richmond, "probably fearing to come back."

Fairfax entered the war divided like the nation itself. That truth is a far cry from the myth that Virginians, including those just across the Potomac from Washington, were solidly in the Confederate camp. The divisions within the Commonwealth demonstrate why we must be careful not to jump to conclusions about the inhabitants of Virginia and other Confederate States during the war.

Note on Sources:

For a good account of Unionist sentiment in Fairfax County, see Charles V. Mauro, The Civil War in Fairfax County: Civilians and Soldiers.