Residents of the District sometimes view the Commonwealth of Virginia as though still belonging to the Confederacy. A few of my DC-based friends have even joked that they need a passport to cross the Potomac and enter the Old Dominion state. Governor McDonnell's original Confederate History Month proclamation did not do much to help matters. However, as even McDonnell was finally forced to recognize, the wartime reality of Virginia is much more complex and nuanced. Nowhere is this more evident than in Fairfax County.

Prior to the start of the Civil War, Fairfax and other parts of Virginia had seen an influx of Northerners, who were attracted by the milder climes south of the Mason-Dixon line. According to the1860 Census, the Northern states with the largest presence in Virginia were Pennsylvania (18,673), Ohio (7,735), New York (4,617), New Jersey (1,611), and Massaschusetts (1,431).

A November 1, 1861 New York Times article on Northerners in Fairfax County observed:

[When] the war broke out. . . they constituted a large and influential class of the population. They settled generally in the eastern part of the county, and are to be found most numerous between Drainsville [sic] and Alexandria. Groups of four or five families are to be found in other parts of the county, and between Centreville and Manassas Northern families are not unfrequently met.

The newcomers helped to improve farming methods and increase agricultural production in an area that had seen its fair share of economic hardship. As the Times reported, "[w]herever a Northern farmer bought a worn out farm two or three years sufficed to bring it up to an excellent condition." Moreover, "[t]he Northern settlers rarely buy slaves, but cultivate their farms with free labor. In some instances, where their sons have married into Southern families, they have become possessed of a negro or two; but in these instances, the relation has generally been one of a voluntary character." (I am not sure what is meant by "voluntary character;" perhaps the Times was trying to rationalize the contiunace of slaveholding by these Northern families.) The Times speculated that Northern industriousness had improved land values in the county. For example, an "estate of one hundred and forty acres, north of Falls Church, was purchased by a Northern man at $8; a year ago it would have readily sold for $75."

|

| American Farm Scenes, No. 2, Currier & Ives, 1853 (courtesy of The Old Print Shop) |

|

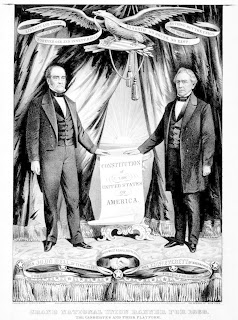

| 1860 campaign poster for the Constitutional Union Party. Presidential candidate John Bell is on the left; Vice Presidential Candidate Edward Everett is on the right (courtesy of Wikipedia Commons) |

As the country headed towards disunion, residents of Fairfax County initially hesitated to embrace secession. At least some of this sentiment is attributable to the presence of Northern transplants, as well as economic dependence on close-by Northern markets. During the election for delegates to the Secession Convention in February 1861, Fairfax's Unionist candidate, William Dulaney, received 57 percent of the vote, compared to the pro-secession candidate, Alfred Moss, with 43 percent. Dulaney was in the minoirty on April 17, when the Convention voted in favor of secession and sent an Ordinace to the voters for ratification. On May 23, 1861, Fairfax voters approved the Ordinance by 76 percent. Only three of fourteen districts (Accotink, Lewinsville, and Lydecker's, in and around Vienna) voted against secession. (See the original voting records here.) The start of hostilities at Fort Sumter and Lincoln's call for 75, 000 volunteers may have generated some of this support, which had grown considerably since the February vote. However, secessionists also intimidated voters at the polls, sometimes by openly threatening violence against pro-Union men. The voting was not by secret ballot, so everyone at a polling station would have known how a neighbor came out on the question of secession. Some voters likely switched allegiances or stayed home rather than risk physical harm to cast a vote against the Ordinance.

|

| "How Virginia Was Voted Out of the Union," Harper's Weekly, June 15, 1861 (courtesy of sonofthesouth.net) |

As the Union Army occupied Northern Virginia in the fall of 1861, the Times reported:

The Northern settlers are almost unanimous for the Union, and though they have suffered great losses by reason of the war, most of them having been compelled to desert their homes after Bull Run, they have aided the Union cause in every way they could. Some are acting as guides, others in various capacities under the Government.The paper also called out Northern transplants who supported the Confederacy, including the postmaster of Falls Church, who was arrested and forced to take an oath of allegiance. The postmaster fled to Richmond, "probably fearing to come back."

Fairfax entered the war divided like the nation itself. That truth is a far cry from the myth that Virginians, including those just across the Potomac from Washington, were solidly in the Confederate camp. The divisions within the Commonwealth demonstrate why we must be careful not to jump to conclusions about the inhabitants of Virginia and other Confederate States during the war.

Note on Sources:

For a good account of Unionist sentiment in Fairfax County, see Charles V. Mauro, The Civil War in Fairfax County: Civilians and Soldiers.

10 comments:

Ron,

The title of your blog is clever.

Re. "secessionists also intimidated voters at the polls, sometimes by openly threatening violence against pro-Union men. The voting was not by secret ballot, so everyone at a polling station would have known how a neighbor came out on the question of secession." What is your source(s)? At the National Archives, I've looked into the claims of intimidation made by some authors who cite the Southern Claims Commission; none withstand scrutiny. While it's true there was no secret ballot anywhere in the US (it wasn’t introduced to the US circa 1890), it is not clear that anyone other than the conductors knew how a man voted. One one source says voters had to shout out their vote so others could hear. It was probably like modern voting where in McLean: you approach the table, the voting official asks for an ID and your name and address. Those behind you in line may or may not hear your responses. Nothing I've read indicates that the voting sheets were available for public review, either. The cartoon from Harper’s is flawed. Nothing in that edition documented claims of intimidation or even mentioned Fairfax County voting. Also, observe that the surprised voter has a slip of paper in his hand, yet as you noted, voting was by voice, a fact the cartoonists missed. You should mention that the unionist delegate, Dulaney, urged his fellow Virginians to support secession in a speech on May 20, 1861. You also should include that Federal troops invaded N. Virginia on May 24, before the official referendum vote count was released by Gov. Letcher in June. I’ve spent months researching the secession vote and assure you it’s wishful thinking for you to write: “Fairfax entered the war divided like the nation itself.”

Thanks for your comment, and I am glad you like the title of the blog.

As I have indicated in the posting, my main source on Union sentiment in Fairfax at the time of secession was Charles V. Mauro, The Civil War in Fairfax County: Civilians and Soldiers. This book draws on the Southern Claims Commission documents you mention. In addition, I looked at the 1969 Yearbook of the Historical Society of Fairfax County, Virginia, Inc., which contains an article on “Secessionist Sentiment in Northern Virginia.” These, and other reliable sources that I have seen, continually reference examples of voter harassment and intimidation during the May 23 voting. For example, the HSFC article notes that “[v]oters were placed under severe pressure at the polls by the viva voce balloting." Mauro indicates that four who voted against the referendum were "persuaded" to vote for it by intimidation. I’d be curious as to why you think the Claims Commission documents do not “withstand scrutiny.”

As for the political cartoon in Harper’s Weekly, it is just that – a political cartoon. Such cartoons do not necessarily relate to an article in the same publication. This cartoon was likely intended to mock the legitimacy of the Virginia referendum vote due to stories of voter intimidation. I used the illustration to show that contemporary sources questioned the vote in Virginia, of which Fairfax County is a part.

Federal troops may have “invaded” before the official announcement of the results of the referendum. Nevertheless, in the weeks between the vote in the Secession Convention and the May 23 vote on the referendum, Virginia mobilized its militia and seized federal facilities, including Harper’s Ferry and Gosport Navy Yard. The Union Army was poised to make its move across the Potomac once the rebellious state took its final official step to join the Confederacy. The outcome of the referendum was no secret. On the night of the 23rd, the citizens of Alexandria feted the results of the referendum vote in the streets, the day before Union occupation. It would have been military folly for the Union to wait until an official announcement.

You state that it is “wishful thinking” on my part to say that Fairfax was divided like the country as a whole. My conclusion is far from fantasy. Even assuming no intimidation, nearly a quarter of the county’s votes cast went against secession, and it is known that there were pockets of pro-Union sentiment in the county, such as near Vienna and in Lewinsville. Hostilities among Union and Confederate sympathizers in Fairfax would continue throughout the war. (See my post on the Hunter Mill Defense League for information about a good documentary on this subject.)

Thanks for the debate!

You wrote, “Mauro indicates that four who voted against the referendum were ‘persuaded’ to vote for it by intimidation.” The footnote associated with persuasion in Mauro’s book is to Conley’s Fractured Land: Fairfax County's Role in the Vote for Secession, May 23, 1861. In that book, the first case was Deavers, of which I’ve already disposed above, leaving at most three other claims of intimidation.

Herewith are analyses of those three cases: #2. “Claim of George W. Steel (sic): ‘When I voted against the Ordinance of Secession John Marshall told me I ought to be shot.’ (Note: His was the only vote against secession in Arundell’s precinct.)” (Conley 7) Analysis: Assuming Marshall made the statement Steele attributes to him it was uttered after Steele voted, so while you might view it as veiled threat, it did not constitute intimidation and didn’t “persuade” Marshall to change his vote.

#3. “Claim of Henry McWilliams: ‘He went to Leesburg to vote against the secession. He went up to the poles and wrote his vote on a slip of paper and handed it to the inspector, who recorded the votes. He looked at it and said, ‘Mac, you are not going to vote this way are you? If you do you are the first man to-day…. He then took back the paper, put it in his pocket and walked off.” (Conley 8) Analysis: (1) Votes were cast by voice not with paper ballots. (2) Daniel Lewis told the SCC that McWilliams was “disloyal and ought not be paid.” (File #4370) (3) The Commissioners were skeptical of McWilliams, “Did McWilliams think it [the SCC] was a good place to get money?” (4) The McWilliams incident occurred at Leesburg and doesn’t belong in a book about Fairfax County. On April 1, 1861, McWilliams lived in Loudoun County. He left Loudoun after First Manassas (File #4370), so he couldn’t legally have voted in Fairfax. (5) McWilliams verbatim recollection of a conversation a decade after the event is remarkable. (6) We are to believe McWilliams turned tail at the inspector’s alleged question, not a threat, just a question.

#4. Conley cites Edward Mayhew as being intimidated. Analysis: (1) Edward Mayhew’s wife, Polly, told the SCC, “He was always a sickly, feeble man, and he didn’t vote at all [in the referendum]. He said he couldn’t vote to suit himself and he wouldn’t vote at all.” (2) John Keene, a unionist, testified before the SCC on June 1, 1876, that Mr. Mayhew told him that when it came to the referendum “that he didn’t vote at all; that he couldn’t vote to suit him.” Mr. Mayhew died in the fall of 1861. Polly probably submitted a claim because she was a widow in a county devastated by the Union Army hoping to get some money from the Feds after the war. Edward’s chronic ill health and dissatisfaction with the voting options account for his “intimidation.” Nothing in the SCC records show anyone persuaded him not to vote. The SCC reduced Polly’s claim by 1/3, because she admitted she was pro-secession and by 2/5 because two of Edward’s sons fought for the Confederacy.

You asked why I believe the SCC documents do not “withstand scrutiny.” The above analyses provide a few examples. As I explained initially, I’ve looked at claims by other authors of intimidation in Fairfax County made before the SCC. When one researches SCC claims one finds some claimants or witnesses actually voted for secession but lied and said he was a unionist, or some witnesses contradict the claimant, or some claimants said a Fairfax cavalry unit intimidated voters, yet one of its members voted against secession (!) and in his testimony to the SCC and other fora never said the unit intimidated a soul, etc.

The Harper’s cartoon isn’t based on any facts and doesn’t prove any intimidation occurred in Virginia. It illustrates nothing except a lack of understanding of voting methods in Virginia. As evidence of intimidation it is worthless.

I accept your acknowledgement that the North invaded Virginia before any vote totals were announced, much less the official numbers. The Federals crossed the Potomac at 2am the morning after the polls closed. Federal intimidation of Virginia preceded the referendum for some time. On April 27, Lincoln announced a blockade of the Confederacy and Virginia, which had not yet seceded. Northern newspapers reported troop build-ups to invade Virginia from multiple directions. On May 18, two Yankee warships shelled Sewells Point in Norfolk. You replied, “in the weeks between the vote in the Secession Convention and the May 23 vote on the referendum, Virginia mobilized its militia and seized federal facilities, including Harper’s Ferry and Gosport Navy Yard.” In fact, the Federal Government burned and evacuated both Harpers Ferry and Gosport. Virginia’s seizure came later. What is your source for writing, “On the night of the 23rd, the citizens of Alexandria feted the results of the referendum vote in the streets”?

You wrote, “nearly a quarter of the county’s votes cast went against secession.” Actually, it was barely 23%, which is a trivial percent of the vote in any election. It hardly justifies you writing “Fairfax was divided like the country as a whole.” By any standard, over 75% in favor of a proposition is a supermajority. According to your reasoning, every election shows a divide, no matter how small the losing vote.

(NOTE: I submitted this before the two latest comments, but I'm not sure it went through. It should precede them.)

Regarding your quote from Mauro’s book: (1)Plaskett was unintimidated because he was voter #57 against secession at Accotink. (2) The threat by Henderson failed to intimidate Deavers from voting against secession. (3) The deposition of William D. Smith in the claim of John W. Deavers to the Southern Claims Commission (SCC) was silent on the both the Plaskett & Henderson incidents. (4) The fact that Accotink voted 19 for vs. 76 against secession makes any claim of intimidation there suspect. (5) Question 23 of the SCC read, “What force, compulsion, or influence, was used to make you do anything against the Union cause? If any give all the particulars demanded in the last question.” Because Deavers sought compensation he may have embellished his answer by claiming Henderson threatened him. His motive to gild his claim? Deavers was “impoverished” according to Edith Sprouse in Fairfax County in 1860: A Collective Biography. “Secessionist Sentiment in Northern Virginia” from the 1969 Yearbook of the Historical Society of Fairfax County doesn’t cite one specific instance of intimidation. It merely asserts, “[v]oters were placed under severe pressure at the polls by the viva voce balloting." There is no footnote substantiating that text. In the case of Accotink, Lydecker’s & Lewinsville precincts, which voted majority unionist, the alleged severe pressure could have suppressed the secessionist vote. Furthermore, the implication is that viva voce was a nefarious secessionist ploy for the referendum. However, it had been the method of voting in Virginia since the colonial era. Secret balloting didn’t exist anywhere in the US in 1861.

Thanks again for your comments.

I did not have the luxury of examining first-hand all of the SCC records in the National Archives, and I understand from Mauro’s book that some claims were possibly exaggerated so that claimants could secure financial rewards. That being said, others have studied the same sources on the secession vote, and arrived at different conclusions from you. Your research does provide an interesting counterpoint, but at times reflects a certain degree of guesswork and conjecture.

Voice voting may have been the standard practice. I did not imply that it was a secessionist plot – I merely meant that the absence of secret balloting at the time made it that much easier to intimidate voters, which is likely one of the reasons our country has adopted the secret ballot. (Incidentally, the HSFC 1969 Yearbook does provide footnoted sources on the Ordinance vote, including the quote on voice voting that I mentioned. It also indicates that intimidation may have influenced the voting.)

The Alexandria celebration anecdote comes from Occupied City: Portrait of Civil War Alexandria by Jeremy J. Harvey.

Finally, 23% may be a substantial minority, as it is in any election. But in reality, all elections do show a divide, just as the Ordinance referendum in Fairfax does. The point of the post was to demonstrate that Faifax was not unanimous for leaving the Union, as some may believe.

Our exchange shows that historical evidence and facts are subject to varying interpretations. In the end, we will need to agree to disagree.

If one thought that one's political opponents would intimidate them at the polls, one way to react to voter intimidation might be to simply avoid the polls.

The overall vote in the Commonwealth in May 1861, was larger than it had been in the Presidential election of November 1860. This would seem to undermine the assertion that there was widespread voter intimidation of Unionists opposing secession.

I would be curious to look at the voting data for Fairfax County in the three elections of November 1860, 4 February 1861, and 23 May 1861.

These data might shed light on the issue of voter intimidation.

Thanks for your comment, Jon.

I agree that one effect of intimidation might be that people stayed away from the polls. There are numerous accounts, including in Southern Claims Commission files, of irregularities during the May 1861 vote. You point out an interesting fact about the total number of voters going to the polls. The larger number, however, could reflect growing enthusiasm on the part of pro-secessionist voters by the time of the Ordinance vote. Perhaps they are the ones who stayed home during the 1860 election, but felt it important to participate in the May vote. I suppose we would need to see more detailed data, as you indicate.

Of course, we will never know one-for-one who may have abstained from voting on the Ordinance that day due to fears of retaliation for voting pro-Union. How do you prove a negative? My post did not mean to suggest that intimidation was the deciding factor. Even without intimidation, the vote likely would have been largely in favor of secession. There are many moderates who switched positions from the Feb. 4 vote to the May 23 one. I hope to explore more of the evidence of intimidation and irregularities here as we head into the 150th anniversary of the Ordinance vote.

Ron,

There has been a good deal of work on Unionism in the Shenandoah Valley by a local journalist going by the nom de plume of Cenantua.

http://cenantua.wordpress.com/

There is a book series on Unionists in the Valley, in which local historians have gone through the Southern Claims Commission, examining the post-war claims of Unionists from Valley counties. Pretty interesting.

Thanks for the information. I've seen Robert Moore's work over at the Cenantua blog, and recently checked out his posts on voter intimidation. When it comes to Unionism and the secession vote, it seems that the Shenandoah Valley has received a lot of attention, as has West Virginia (formerly the western counties of Virginia).

Given the focus on SCC claims documents, I wonder how many other primary materials are out there that speak to intimidation and its effects. For example, are there many news articles and diaries? In researching, I've noticed that a lot of times there are descriptions of threats, but that the impact of these threats on non-voters is hard to gague.

Post a Comment