|

| General Robert Schenck (courtesy of Library of Congress) |

|

| Col. Maxcy Gregg (courtesy of Wikipedia) |

I marched the troops back, placing the two 6-pounder guns on the hill commanding the bend of the railroad, immediately supported by Company B, First South Carolina Volunteers. . . . . The rest of the regiment . . . was formed on the crest of the hill to the right of the guns. The cavalry were drawn up still farther to the right. (Gregg Report, OR, Series 1, Vol. 2, Part 1, p. 129.)As the 1st Ohio turned the curve outside of Vienna, the Confederate battery opened fire with shot, shell, and grapeshot. The first platform car was untouched, but the second and third cars received the deadliest fire. The train encountered some mechanical difficulties, and the engineer could not pull the train out of range of the guns. (By some accounts, the breaks had locked when the engineer slammed them at the outset of the attack.) The soldiers, coming to the realization that they were sitting ducks, "left the cars, and retired to right and left of [the] train through the woods." (Schenck Report, OR, Series 1, Vol. 2, Part 1, p.126.) Meanwhile, to Schenck's disgust and amazement, the engineer "instead of retiring slowly, as I ordered, detached his engine with one passenger car from the rest of the disabled train and abandoned us, running to Alexandria." (Schenck Report, OR, Series 1, Vol. 2, Part 1, p.126.) Believing that his force was badly outnumbered by as many as 1,500 Confederates, Schenck threw skirmishers out along his flanks and retired towards Arlington. Without the train, his men were forced to carry the wounded on litters or in blankets.

|

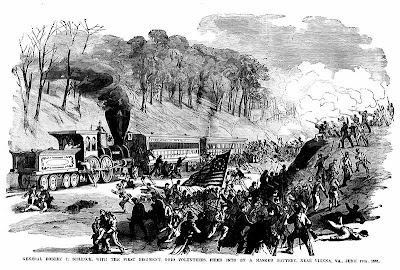

| Fanciful sketch of the Battle of Vienna, from Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper (courtesy of Wikipedia) |

A Unionist from Vienna eventually loaded six of the dead into his wagon and took them to Schenck's camp. In all, Schenck reported eight dead and four wounded in the engagement. The casualties came entirely from Companies G and H, which had been positioned on the second and third rail cars.

In the immediate aftermath of the skirmish, McDowell wanted to move in force upon Vienna. As he wrote in his official report, "[h]ad the attack not been made, I would not suggest this advance at this time; but now that it has, I think it would not be well for us to seem even to withdraw." (McDowell Report, OR, Series 1, Vol. 2, Part 1, p. 125.) General-in-Chief Winfield Scott, however, opposed the idea of sending more troops in the direction of the town. He would soon recall Brigadier General Daniel Tyler from an advanced position at Falls Church, which Scott viewed as too exposed and vulnerable.

The news of the skirmish at Vienna spread across the North. The New York Times was particularly critical of the defeat, which followed closely on the heels of the Union loss at Big Bethel. According to a June 20, 1861 article, a local man had flagged the train near Vienna and warned the 1st Ohio of an impending disaster, but Schenck did not halt the train or prepare his soldiers for an attack. (Schenck makes no mention of this episode in his report.) The Times also questioned the failure of the Union force to send scouts or skirmishers ahead of the train to ascertain any dangers. As the Times wrote on June 19:

In the present case an entirely inadequate body of men was actually within the enemy's lines, in a railroad train, with no more careful exploration of the country than a traitorous engineer, or an accidental glance from a car-window, might furnish. . . . Surely, the simplest knowledge of military matters must condemn so heedless a movement as to the last degree reckless and unscientific, and may fairly sit in judgment upon those who planned it. The entire policy of these detached and apparently purposeless expeditions is questionable. If they are understood to be what are technically known as reconnaissances in force, they should have force in the possession of flying-artillery, and dragoons. To enter upon doubtful territory, where the enemy may be in the greatest strength, without precaution, is simply foolhardiness.Such reporting fed concerns about the preparedness of the Union volunteers camped around Washington. As journalists dissected the action at Vienna, however, the Union high command was busy contemplating its next move.

Note on Sources

The Battle at Bull Run by William C. Davis and The Glories of War: Small Battles and Early Heroes of 1861 by Charles P. Polland, Jr. contain fairly detailed accounts of the Battle of Vienna.

4 comments:

Great job...just posted this to the Fairfax Civil War Facebook page!

Thanks! I am glad you liked it, and I appreciate you letting others know.

I tip my hat to you Ron...Ditto's to the previous comment.GREAT JOB..After reading the account of Vienna, I thought I could smell gun power....Jim (Michigan)

Thanks, Jim. Glad you enjoyed the post.

Post a Comment